Architectural Digest

ARCHITECTURAL DIGEST

By Nick Mafi, Photography by Ye Rin Mok

Inside the Venice Beach Bungalow of a Former Apple Design Lead

For industrial designer Christopher Stringer and his wife, artist Elizabeth Paige Smith, designing the perfect home meant filling it with objects from their lives

Most people want the design of their home to be the very antithesis of their workspace. But industrial designer Christopher Stringer and his wife, artist Elizabeth Paige Smith, aren’t like most people. The creative duo wanted their dwelling to closely reflect their professional lives. “We’re fortunate because we have obsessions that happen to be our jobs,” says Stringer, a former top designer at Apple. “And the design of our home, the way we live in it, it seeps into our work.” But first, they had to find a home that could match their bold style.

After meeting in 2008, Stringer and Smith moved from L.A. to the Bay Area. “We spent about a decade in seclusion up there,” Smith quips. The artist, who is a self-described beach girl, thought Southern California would be perfect place to find a new home. “I lived [in L.A.] after school, and Chris has always felt a kindred spirit in the area, particularly Venice.” Which is precisely where the couple looked to buy a weekend getaway. Through a friend in real estate, they happened upon a 1927 California bungalow in Venice. “The moment we saw it, we thought, ‘This is exactly what we’ve been looking for,’” Stringer explains.

In 2018, after two years of renovation, the couple decided to turn the home into their primary residence. “We fell in love with it as something that wasn’t intended as our full-time residence,” Stringer says. “But we experienced a noticeable lifestyle change in this home. It became our sanctuary.” The couple felt it was important for the home to maintain its quintessential Venice Beach architecture. They didn’t touch the exteriors, and instead they shifted their creative rigor to the interiors of the space.

“We both felt a really strong desire to preserve the house, maintaining its original bones. We were not interested in building a box, as the newer developed homes here tend to strip away a lot of the culture of Venice,” Smith explains. This meant creating ephemeral and almost glowing rooms filled with cedar, walnut, and mahogany wood, Smith’s stunning art, and Stringer’s eye for aesthetic yet functional design. (Before he left Apple in 2017, Stringer greatly contributed to the design of the PowerBook, iMac, iPod, iPhone, iPad, MacBook, Apple Watch, Apple Pencil, and HomePod. Nowadays, his triphonic speaker design, Syng, is what’s making waves, and those globular fixtures make a few appearances in the home.)

Designing the interiors for two ultra-creative people would prove to be the major task in transitioning this home from a charming Venice abode into a highly stylized space. “The house is the chain of experiences we bury ourselves in, how we want to feel, where we want to be, how we build the story of the day,” Stringer says. “We really resonate with waking up with natural light, so above our bed we carved out a skylight. This starts our day with the sky straight overhead, which may sound invasive, but it gives us a signal of what the day is going to be like.”

If the second-floor primary bedroom is full of natural light, the first floor is more muted and intimate. “Christopher grew up in Australia, and I grew up on an island, so we’re both drawn to the idea of these remote oases,” says Smith, who was raised in the Cayman Islandsbefore going to the University of Kansas (or as she says, “moving from one island to another”). “We were conscious of maintaining the original garden windows throughout the first floor,” Smith continues, “which not only draw the light in, but also bring more of the nature in as well. This, in effect, is not only a response to the original architecture, but also to our shared upbringings.”

Though the couple is fully aware that the interiors they’ve designed are intended for their usage in the moment, both feel the history of the nearly century-old space. “Sometimes when I look at a part of the home, I think, ‘Perhaps this is getting closer to the feel of how it was originally intended,’” Stringer says. “We all participate in every part of a home to different degrees, but there’s this constant rigor to get to the sense of feeling that every space is right.”

1/16

Homeowners Christopher Stringer and Elizabeth Paige Smith stand by their front entrance, which consists of tri-fold doors by La Cantina. Above them is a ceramic overhead lighting by Stan Bitters. Redwood steps lead into the entryway.

2/16

The family dog, Woody (an Australian cattle dog), sits near Venice shoe rack shelves in solid mahogany wood by artist and homeowner, Elizabeth Paige Smith.

3/16

A tripod book stand by Marc Newson holds a David Hockney book published by Taschen. In the garden window, custom ceramic Thumb pots are by Smith.

Art: Elizabeth Paige Smith.

4/16

The primary bedroom features a DC Bed by Vincenzo De Cotiis, sheets and a throw by Parachute, a custom goat skin rug by Pure Rugs, and a fan by Boffi. The custom-built Infinite Vibrations Mirror was designed by Smith, as were the three crystal lights (in collaboration with Robert Lewis Lighting). The star of the bedroom, however, is the custom-built steam shower, which was designed by the homeowners. Above the steam shower is a skylight that, with a click of the button, opens to the outdoors. “When you’re in there, it’s like you’re in a courtyard. But really, you are outside, in the middle of the bedroom,” Stringer says.

Art Left: Mulga the Artist. Art Right: Paul McNeil.

5/16

The study features a Chevron Writing Table in Aqua and Custom Chess Board, both by Smith. The vintage chess pieces are by Carl Aubock.

Art: Elizabeth Paige Smith.

6/16

Inside of the zen room, artwork by Smith adorns the walls. The ceramic ceiling lighting was made by Stan Bitters, and it gives the walnut flooring and cedar wood walls a calming amber glow.

8/16

The dining room consists of a mahogany wood and stone top table, a chess board designed by Smith, and a hanging ceramic artwork by Heather Levine.

9/16

The guest room features a Pyramid Commode in mahogany by Smith, a hunting chair by Borge Mogensen, and drapery and upholstery on the wall by Romo.

10/16

The primary suite includes a Ofurò bathtub by Rapsel, designed by Matteo Thun & Antonio Rodriguez. The artwork is by Smith. The bath towels are by Parachute.

Art Left: Crowds with Shape of Reason Missing: Example 3, 2012 © John Baldessari. Courtesy Estate of John Baldessari © 2022 Courtesy Sprüth Magers.

11/16

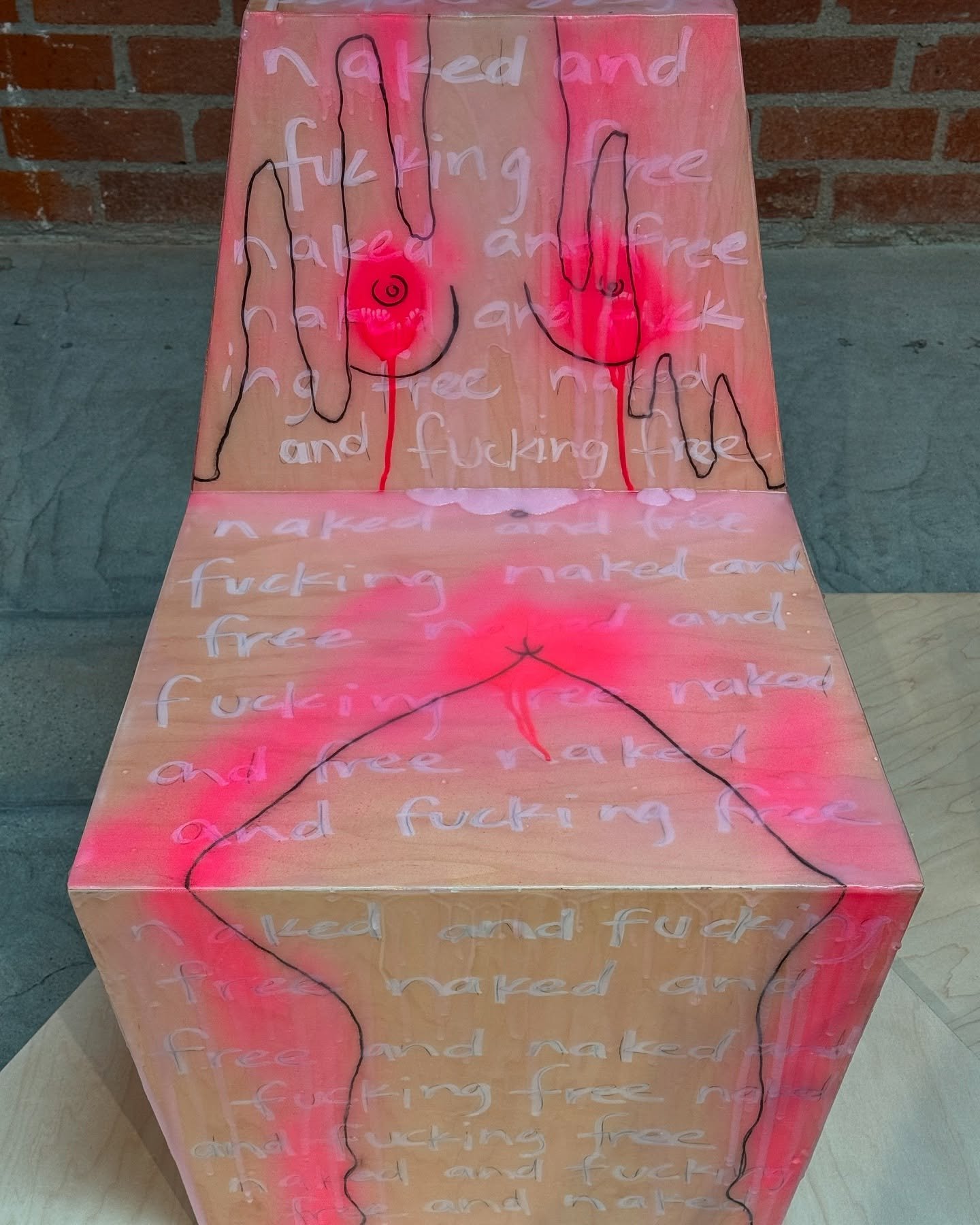

The living room includes a sofa designed by Francesco Binfaré and Stringer’s Syng Cell Alpha speakers. There’s a nude dining chair in chocolate by Smith. An original 1970s Gufram Green Cactus coat rack adds a vibrant splash of color.

12/16

This powder room features both a Venice Vanity I in California Calcutta stone and mahogany wood, and a piece from the Infinite Vibrations III mirror series by Smith.

13/16

This corner includes the homeowner’s work: a natural leather custom bench by Smith and a Syng Cell Alphaspeaker by Stringer.

14/16

Inside the kitchen is a vintage iron and leather wine rack by Arthur Umanoff sitting atop custom milled California Calcutta stone.

15/16

The living room includes Alchemy Sound Bowls that sit atop Smith’s White Diamond table, a Pouf chair, and a cowhide rug by Pure Rugs.

16/16

The hammock (sourced through Coquicoqui) draws in the eye as a nouveau hearth in the room. A yellow pedestal table and blue pedestal table, both by Smith, add splashes of color.